From my point of view, it's impossible to delve deeply into JavaScript without understanding at least these three fundamentals/concepts that shape the language's foundation.

Syntax Parser

Initially, any regular language (such as programming languages) can be identified by a set pattern of structures and rules. Imagine a curious conversation between a father and son, where the son asks the following innocent questions:

- Father, what is text?

It's a collection of paragraphs, son.

- And what are paragraphs?

It's a collection of sentences.

Hmm... and what are sentences?

Well, a sentence is a collection of words. And, finally, words are collections of letters separated by spaces or special characters.

Ham 🤔

Father, so if I put any letters together, will I have words?!

Right then, you grasp how crucial it is to have a proper sequence of letters and some basic rules to make actual words. Letters only become words if they're in the dictionary, am I right? This matching or mapping process creates what we call a token.

And here we reach an important point, the creators of a regular language are responsible for defining the tokens and their meanings. Just as the token "Olá" means a greeting in the Portuguese dictionary.

In the case of JavaScript, the ECMAScript is responsible for managing all these tokens and ensuring that the code you write in your IDE will undergo an evaluation according to the created rules. IDEs use LSPs (Language Server Protocol) to consult the rules and, for example, underline in red a set of unidentified letters. But hey, that's a story for another day!

Finally, this is where the Syntax Parser comes in, it is a part of Javascript engine responsible for analysing each character of your code, identifying tokens by lexical operators, checking if the grammar is correct or not trough syntax analisys, and then generating what we call an AST (Abstract Syntax Tree).

After that, there's some behind-the-scenes magic to turn it all into machine instructions, but let's keep it breezy for now. Btw, this is the ECMAScript Language: Statements and Declarations or we can say "Javascript Dictionary”.

I recently discovered this website which shows how the representation of the language would look like in AST format.

For example, pick JavaScript, throw in a variable like "foo":

// javascript code

const foo = 'bar';And ta-da! You get this cool tree of tokens in JSON flavour.

// AST using JSON format

{

"type": "Program",

"start": 0,

"end": 18,

"body": [

{

"type": "VariableDeclaration",

"start": 0,

"end": 18,

"declarations": [

{

"type": "VariableDeclarator",

"start": 6,

"end": 17,

"id": {

"type": "Identifier",

"start": 6,

"end": 9,

"name": "foo"

},

"init": {

"type": "Literal",

"start": 12,

"end": 17,

"value": "bar",

"raw": "'bar'"

}

}

],

"kind": "const"

}

],

"sourceType": "module"

}Lexical Environment

"Lexical” means “having to do with words or grammar”. So we are talking about the code you are writing properly, the syntax and vocabulary. Now, a lexical environment exists in programming languages in which where you write something is important. So, basically, the parser keeps an eye on where you put stuff.

Let's take a look at a function with an internal variable:

function potato() {

var food = "potato";

}The variable food is nestled within the function potato at a lexical level — that's its place within the code you're creating. But as we've learned, your code doesn't directly land in the computer; instead, the Syntax Parser translates it into something the computer comprehends. Nonetheless, based on where the code resides, we can get a sense of location in the computer's memory and how it will interact with other variables, functions, and elements of the program.

So, when we are talking about the lexical environment of something in the code, we are talking about where it is written and what surrounds it, got that? If so, now we can move on to the final topic and connect everything you’ve been reading so far.

Execution Context

I like the simple definition: a wrapper to help manage the code that is running. In the real project, there are a lot of lexical environments (areas of the code that you are looking at physically), which one is currently running is managed via execution contexts. They can also contain elements beyond what's explicitly written in your code.

When a function or script runs, the JavaScript interpreter generates a new context. Each script or function starts with a fundamental context known as the global execution context. Whenever a function is invoked, a fresh execution context is formed and stacked on top of the execution stack. This same sequence occurs when delving into nested functions that call other nested functions. JavaScript operates within two scopes: Global Scope and Local Scope.

Just a friendly reminder:

- Name/Value pair is a name which maps to a unique value. Now that name may be defined more than once, but it can only have one value in any given context. Remember we're talking about execution context. So in any particular execution context, that is, a section of code that is running, a name can only exist and be defined with one value.

// name (variable) and the value Ferrari const carName = "Ferrari 488"; - And an object is a collection of Name/Value pairs. That's the simplest possible definition of an object when you're talking about JavaScript. Other programming languages might have more complex concepts when it comes to objects, but when we're dealing with objects in Javascript, that's really what they are.

// object with a collection of names (properties) and values const car = { name: "Ferrari 488", production: 2015, engine: { name: "V8", ccPower: 3902, } };

To link these three topics — Syntax Parser, Lexical Environment, and Execution Context — and lay the groundwork for more advanced topics like hoisting and closures, let's check under the hood what the engine offers, even if you haven't written a single line of code.

Global Environment and Global Object

In conclusion, the global execution context automatically generates two components for you without needing them explicitly defined in your code. It crafts a Global Object and sets up a special variable known as 'this'. This occurs because your code is enveloped within an execution context, and the JavaScript engine takes care of these tasks whenever your code runs.

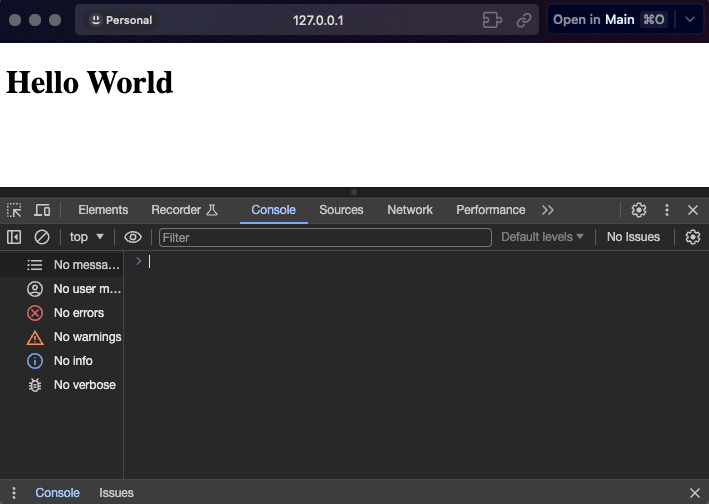

Let's check this simple HTML page referencing a single script named foo.js.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<body>

<h1>Hello World</h1>

<script src="foo.js">

</script>

</body>

</html>And now, this is our foo.js code example:

// there's nothing here... sorry buddy xD

If we serve the HTML, open the browser, and head to the devtools in the "console" tab, you'll notice no errors displayed:

The JavaScript file loaded, the syntax parser initiated, and found nothing to parse. Even though there was no code to execute, the JavaScript engine started the process, resulting in the creation of an execution context (you already know that). Recall the two components that were automatically generated: a global object and a unique variable named this.

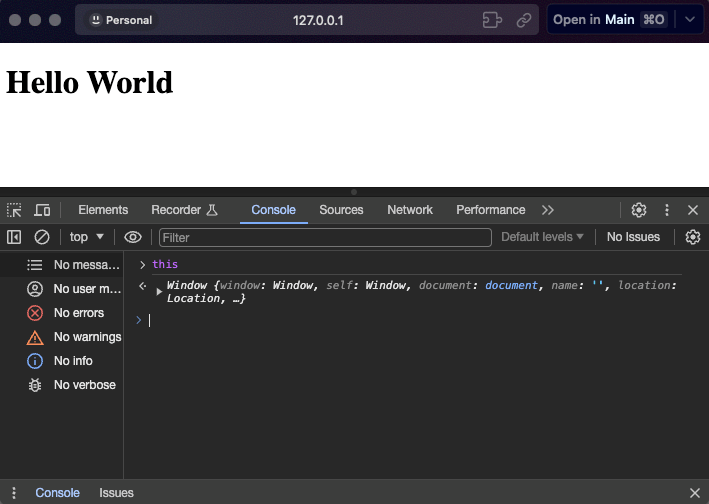

You can take a sneak peek into the execution context by typing this in the console:

The engine determines that the value of this is set to window when JavaScript runs in the browser. This window object serves as the global object within browser environments. Conversely, when the code runs on a server using Node.js, the global object is named "global".

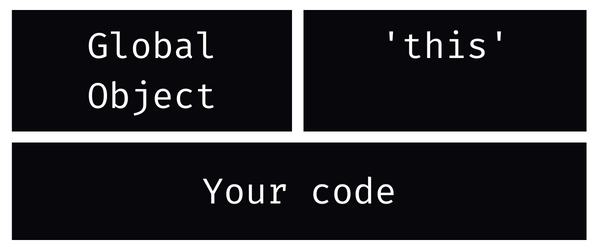

Basically, in a global scope we have:

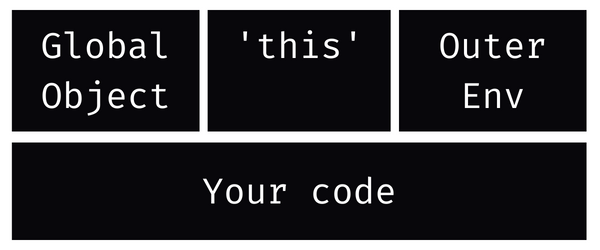

And, in a local scope (inside a function) we have the reference to outside, I mean, the external environment, got it?

So, we just learned something. When we start running code, an "execution context" is formed at the global level. This context includes a global object that's accessible to all code within that window or lexical environment. Inside this execution context, there's a specific variable, 'this', which the JavaScript engine generates. In internet browsers such as Google Chrome or Firefox, the global object is the 'window' object, and it also contains the 'this' variable. At the global level, both the global object and 'this' refer to the same thing.

Conclusion

In the funny dance of JavaScript execution, the Syntax Parser kicks off the show by meticulously analysing the code, guiding the creation of an execution context within its respective lexical environment. This environment houses variables and functions, including a global object, tailored to the environment in which the code operates — be it a browser with its 'window' object or a Node.js server with 'global'.

With a good grip on syntax parser, lexical environments, execution contexts, and the ins and outs of the global object, you're all set to dive into any JavaScript topic. These concepts lay a sturdy groundwork, opening doors for a deeper dive into mastering the language.